An enormous black hole one hundred thousand times more massive than the sun has been found hiding in a toxic gas cloud wafting around near the heart of the Milky Way.

If the discovery is confirmed, the invisible behemoth will rank as the second largest black hole ever seen in the Milky Way after the supermassive black hole known as Sagittarius A* that is anchored at the very centre of the galaxy.

Astronomers in Japan found evidence for the new object when they turned a powerful telescope in the Atacama desert in Chile towards the gas cloud in the hope of understanding the strange movement of its gases. Unlike those that make up other interstellar clouds, the gases in this cloud – including hydrogen cyanide and carbon monoxide – move at wildly different speeds.

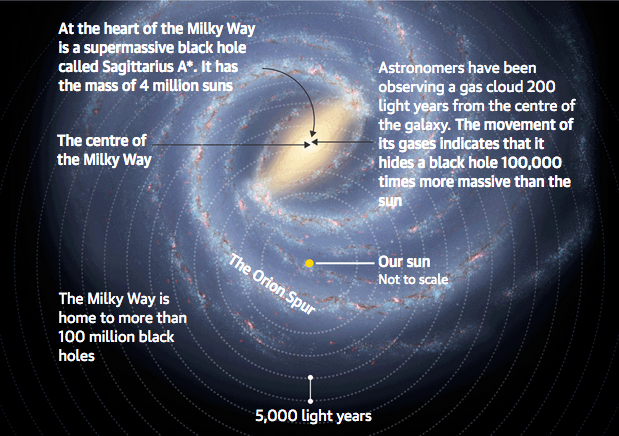

Observations from the Alma telescope in Chile showed that molecules in the elliptical cloud, which is 200 light years from the centre of the Milky Way and 150 trillion kilometres wide, were being pulled around by immense gravitational forces. The most likely cause, according to computer models, was a black hole no more than 1.4 trillion km across.

The scientists’ suspicion that a black hole lay in the midst of the gas cloud received a boost when further observations picked up radio waves indicative of a black hole coming from the centre of the cloud, said Tomoharu Oka , an astronomer at Keio University in Tokyo. “This is the first detection of an intermediate-mass black hole candidate in the Milky Way galaxy,” he said.

So-called intermediate-mass black holes fill a gap in astronomer’s knowledge of the most massive objects in the universe. The smallest black holes form when particular types of stars explode at the end of their lives. According to scientists’ calculations, the Milky Way is home to about 100m of these smaller black holes, though only about 60 have been spotted.

But astronomers also know that much larger, supermassive black holes lie at the heart of large galaxies including the Milky Way, where Sagittarius A* weighs as much as 4 million suns. What is unknown is how these supermassive black holes form.

One theory is that smaller black holes steadily coalesce into larger ones and these come together to form supermassive black holes at the hearts of galaxies, but until now, no definitive evidence for intermediate mass black holes has been found. The detection of a potential black hole weighing as much as 100,000 suns is precisely the middle step in the process that astronomers have sought.

Oka, whose research is published in the journal Nature Astronomy, said the newly-found black hole could be the core of an old dwarf galaxy that was cannibalised during the formation of the Milky Way billions of years ago.

Brooke Simmons at the University of California in San Diego, who was not involved in the study, described the research as “careful detective work”.

“We know that smaller black holes form when some stars die, which makes them fairly common,” she said. “We think some of those black holes are the seeds from which the much larger supermassive black holes grow to at least a million times more massive. That growth should happen in part by mergers with other black holes and in part by accretion of material from the part of the galaxy that surrounds the black hole.

“Astrophysicists have been collecting observational evidence for both stellar mass black holes and supermassive black holes for decades, but even though we think the largest ones grow from the smallest ones, we’ve never really had clear evidence for a black hole with a mass in between those extremes,” she added.

All of which points to the fate that awaits the newly-found black hole. In time, Oka said, the object will be drawn towards Sagittarius A* and sink into it, making the supermassive black hole at the heart of the Milky Way even more massive.